The Cell Phone Debate: Is Fear of Technology Anything New?

For the past 30 years, as technology’s developed, we’ve moved on from Myspace to Instagram, Nokia to Iphones, Napster to Spotify, and fear Y2K to fear of COVID-19. As the abilities of our tech and our dependence on it has grown, there have been many critiques of the new, technocentric culture modern life demands. Cited instances of bullying, more demanding work, anxiety, and ignorance have increased and been pinned on the buzzing little blocks in our pockets. And while many of these negatives do and will continue to exist as technology develops, many people fail to realize how many times these fears have occurred throughout human history. So even though we have been living in “unprecedented times,” the fear of technology is something all too recognizable.

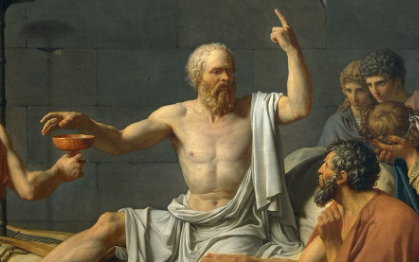

One of the earliest critiques of technological development was actually in response to one of man’s oldest tools; the written word. As philosophical texts were written down in the Hellenic alphabet, as were many epics and government texts, and literacy became more common (although by no means universal), famed philosophers like Socrates and Plato argued that the ability to read and write down one’s thoughts would make society stupid. Socrates, for one, felt that reading philosophy meant that the words would be too open to interpretation and the philosopher’s true meaning would be lost. Additionally, he thought trying to learn on one’s own could never match the relationship between student and teacher and was not an adequate substitute for face-to-face learning. Although this is a sentiment many teachers can agree with, it’s hard to argue that the development of the written language turned out to be as harmful as the Greeks said, in fact, most would say it is a net positive for society. The use of writing is actually how sociologists determine the level of development a civilization has. So even though people worried that technological growth would “make people stupid,” it actually helped expand humanity’s ability to understand and share knowledge.

One of the earliest critiques of technological development was actually in response to one of man’s oldest tools; the written word. As philosophical texts were written down in the Hellenic alphabet, as were many epics and government texts, and literacy became more common (although by no means universal), famed philosophers like Socrates and Plato argued that the ability to read and write down one’s thoughts would make society stupid. Socrates, for one, felt that reading philosophy meant that the words would be too open to interpretation and the philosopher’s true meaning would be lost. Additionally, he thought trying to learn on one’s own could never match the relationship between student and teacher and was not an adequate substitute for face-to-face learning. Although this is a sentiment many teachers can agree with, it’s hard to argue that the development of the written language turned out to be as harmful as the Greeks said, in fact, most would say it is a net positive for society. The use of writing is actually how sociologists determine the level of development a civilization has. So even though people worried that technological growth would “make people stupid,” it actually helped expand humanity’s ability to understand and share knowledge.

In terms of phone addiction distracting people from important tasks and jobs, but this anxiety has been noted in response to another distracting form of entertainment: books. In the 18th century, an increase in publication production and education meant that the children of the upper classes were spending long hours reading novels instead of doing chores or practicing practical skills. For men, this meant neglecting studies and exercise, and for women it meant not practicing sewing, doing laundry, or cooking. For all youth, this meant ignoring parents in favor of curling up with a novel. While this seemed to be one of the largest problems of the day, reading ultimately become an intrinsic part of life and culture. Many of the books we consider “classics” today were seen as populist when they were written. But the culture they were surrounded by truncated them into drivel distractions.

In terms of phone addiction distracting people from important tasks and jobs, but this anxiety has been noted in response to another distracting form of entertainment: books. In the 18th century, an increase in publication production and education meant that the children of the upper classes were spending long hours reading novels instead of doing chores or practicing practical skills. For men, this meant neglecting studies and exercise, and for women it meant not practicing sewing, doing laundry, or cooking. For all youth, this meant ignoring parents in favor of curling up with a novel. While this seemed to be one of the largest problems of the day, reading ultimately become an intrinsic part of life and culture. Many of the books we consider “classics” today were seen as populist when they were written. But the culture they were surrounded by truncated them into drivel distractions.

Another stressor accompanied by the mobile phone is “constant contact.” Especially since the pandemic, the requirement to be available for work while at home or on your days off. This often means longer hours and lower pay for many people. Interestingly, this is not the first time tech advancements have led to a busier schedule. Increases in labor have been seen after the invention of the cotton gin, the plow, the assembly line, and most shockingly, the lightbulb. Gas lighting was first placed in factories in 1805, and expected hours increased nearly immediately. Before the use of lightbulbs, candles were used to light industrial factories. However, candlelight only went so far, meaning people could only work until sundown. More than this, there was very little street lighting and not much public transport, meaning if people wanted to walk home, they would have to leave work before the sun set. After industrial lighting developed, work days increased to the 12 and 14-hour shifts characteristic of the industrial revolution. Hours particularly increased in textile factories, in which precise stitching was required and lighting more necessary. It was collective action and labor reform that ultimately created changes in labor expectations, calling into question whether it is really technology that causes work stress, or the system we work under.

Another stressor accompanied by the mobile phone is “constant contact.” Especially since the pandemic, the requirement to be available for work while at home or on your days off. This often means longer hours and lower pay for many people. Interestingly, this is not the first time tech advancements have led to a busier schedule. Increases in labor have been seen after the invention of the cotton gin, the plow, the assembly line, and most shockingly, the lightbulb. Gas lighting was first placed in factories in 1805, and expected hours increased nearly immediately. Before the use of lightbulbs, candles were used to light industrial factories. However, candlelight only went so far, meaning people could only work until sundown. More than this, there was very little street lighting and not much public transport, meaning if people wanted to walk home, they would have to leave work before the sun set. After industrial lighting developed, work days increased to the 12 and 14-hour shifts characteristic of the industrial revolution. Hours particularly increased in textile factories, in which precise stitching was required and lighting more necessary. It was collective action and labor reform that ultimately created changes in labor expectations, calling into question whether it is really technology that causes work stress, or the system we work under.

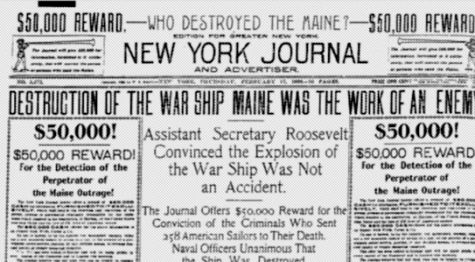

Another frequent critique of the internet is the spike in “fake news,” or stories blown out of proportion to fulfill a certain viewpoint or political ends. Once again, this is a case of history repeating itself. The increase in printing from 1910-1940 meant newspapers could print cheaply and seek profit. This also meant they were in constant competition with each other to gain readership. This is why this period saw one of the first instances of “yellow journalism,” or exaggerated stories meant to attract attention. Only the expensive, upper-class newspapers, like the New York Times could afford to print objective, analytical news, compared to the cheaper New York Journal, which needed to make stories seem as interesting as possible to make any money. Though the time of reporting on the Stock Market Crash and sinking of the Lusitania has passed, this phenomenon still occurs today. The New York Times still requires a subscription to read, while Apple News and all of the cable channels that share their stories on it remains free on the App Store.

Another frequent critique of the internet is the spike in “fake news,” or stories blown out of proportion to fulfill a certain viewpoint or political ends. Once again, this is a case of history repeating itself. The increase in printing from 1910-1940 meant newspapers could print cheaply and seek profit. This also meant they were in constant competition with each other to gain readership. This is why this period saw one of the first instances of “yellow journalism,” or exaggerated stories meant to attract attention. Only the expensive, upper-class newspapers, like the New York Times could afford to print objective, analytical news, compared to the cheaper New York Journal, which needed to make stories seem as interesting as possible to make any money. Though the time of reporting on the Stock Market Crash and sinking of the Lusitania has passed, this phenomenon still occurs today. The New York Times still requires a subscription to read, while Apple News and all of the cable channels that share their stories on it remains free on the App Store.

Technology has a lot of negatives and gives a lot of reasons to complain, but it’s nothing our forefathers haven’t complained about already. All of the things so intrinsic to our lives today, from books and wild tabloids, to light bulbs and cotton underwear, wear once new and scary technology. Although cell phones may seem like the biggest problem facing teens today, it’s nothing society hasn’t faced already. There are far more important, far more scary things than cell phones facing our future generations. Fear, like all things, is cyclical.